Here we explore why GM cotton has become so controversial, and what the future holds for this murky industry.

Take a look at what you are wearing right now, and chances are you’ll see, at least some cotton clothing. Even if you are still in bed, I’ll bet those comfy sheets are made of cotton fabric too. Yet, we have probably never asked ourselves: where does this cotton come from, and at what environmental cost?

For the textile industry it’s impossible to underestimate the importance of cotton. This humble crop accounts for more than half of all global textile requirements. That’s approximately 26 million tons per annum, which works out at 3.7 kg of cotton fabric per person. And perhaps you’ll be surprised to find that GM cotton accounts for more than 90% of this output.

Cotton production in India alone hit 5.77 million tons last year, the highest in the world, followed by the US, China, Brazil, Pakistan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan. The cotton industry is truly far reaching, providing income for more than 250 million people and employing up to 7% of all labor across some of the world’s poorest regions.

It’s a real juggernaut of an industry, with an intricate web of vested interests.

The problem is that all this demand, and the financial incentives associated with it, have stretched farmers and environmental systems to their limit, turning cotton fabric production into one of the world’s dirtiest industries.

[Want to do your bit to make fashion more sustainable? Start here with our ethical clothing search engine - making ethical choices a little bit easier.]

The Dark Side Of Conventional GM Cotton

The total area of land used for cotton farming has not actually changed a lot since the 1930’s, meanwhile production volumes have increased exponentially. What has changed is that nowadays the majority of cotton is grown in dedicated monocultures, using synthetic pesticides, irrigation, and GM cotton plants. A type of intensive farming designed for maximum yield, without consideration for the natural resources needed to sustain it.

Cotton’s water footprint

To put it simply, cotton is a very thirsty crop, using an average of 10,000 litres of water to produce just one kilo of fabric. However, not all countries are equal when it comes to water. In drier regions of India, for example, the amount of water required per kilo has reportedly reached a staggering 22,500 litres. During 2013 cotton production in India used enough water to meet the daily needs for 85% of the 1 billion strong population, for a whole year.

This situation is of course man made. In order to meet increased demand for the export market traditional cotton farms in many developing countries have switched to growing intensive monocultures in order to maximise yields. These dense plantations require constant irrigation, which is usually facilitated by man made channels that draw fresh water away from natural resources such as lakes and underground reservoirs.

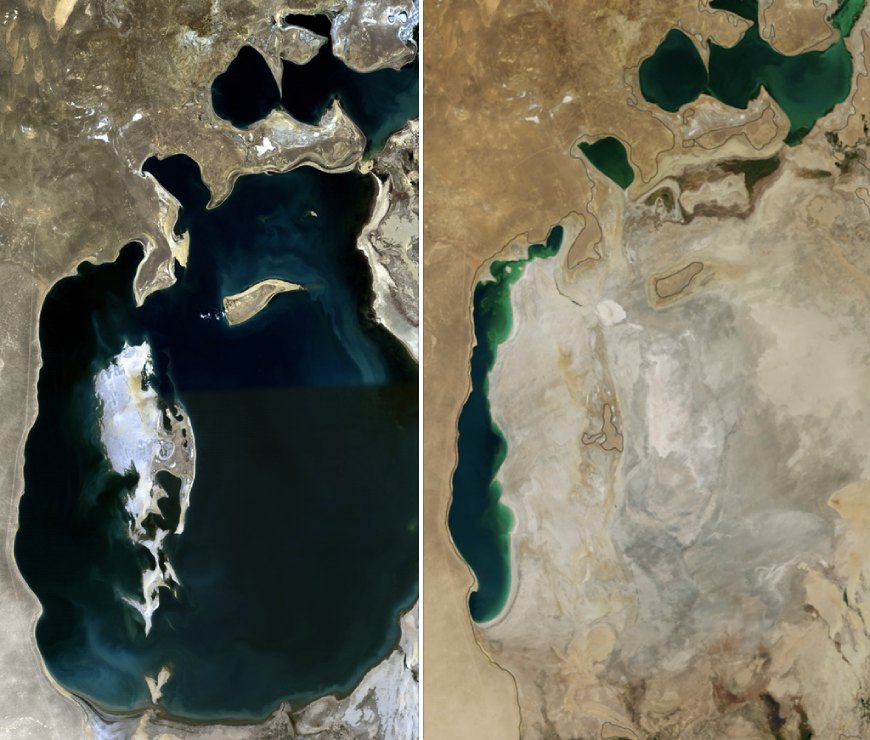

In certain areas the sheer volume of water stolen for the production of cotton is distressingly evident. The Arial Sea in Central Asia, once the world’s 4th largest lake, has all but dried up, for the main part due to a vast irrigation system that feeds 1.47 million hectares of cotton plantations in the surrounding area [insert pic]. What’s even more frustrating is that up to 60% of irrigated water is actually lost before it reaches the cotton plantations due to poor infrastructure.

These jaw dropping figures not only show the scale of the problem, but also that variations in geography, and farming practices play a crucial role in the extent of the problem. Some areas simply don’t lend themselves to the cultivation of cotton, and by forcing nature’s hand we are often taking water directly from the mouths of those that need it the most.

GM cotton and pesticides

When discussing modern cotton production we cannot ignore the issue of genetic modification. The fact is ‘normal cotton’ means GM cotton, and this means Bt Cotton, one of Monsanto’s most infamous products. Nowadays Bt cotton accounts for more than 90% of all cotton grown in the US, India, and China.

Briefly, the ‘Bt’ part refers to a type of Bt toxin taken from a bacterium, which has been inserted into the genome of cotton plants, enabling them to produce this Bt toxin for themselves. Crucially, the Bt toxin is a natural insecticide, meaning that Bt cotton has resistance to the larvae of many insect species, including cotton bollworms, the most prolific pest of cotton plantations.

In theory, by protecting plants from the worst pest species Bt cotton reduces the need for toxic pesticides, which in turn promotes biodiversity by protecting non-target species like ladybugs and spiders. Pest resistance also helps increase yields, and more cotton means more profit, which was supposed to improve the livelihoods of farmers. Sounds good right?

In practice however, it’s not so simple. Since its introduction to India in 2002, there has been a stream of contradictory reports about Bt cotton, ranging from it being an unmitigated disaster through to a triumph of innovation, depending on who you speak to of course.

There is no doubt that Bt cotton was initially very effective at controlling bollworm, and for a period of time this did result in increased yields, and a temporary reduction in the use of broad spectrum pesticides. But this honeymoon didn’t last long.

In India, numerous farmers found that the pink bollworm species rapidly developed resistance to Bt cotton, actually becoming an even worse problem than before. Plus, mounting evidence suggests that Bt cotton was actually less resistant to other pest species from the very beginning, allowing these secondary pests to proliferate in place of bollworm as more and more farmers adopted this variety of GM cotton.

In northern China you can actually track the increase of Bt cotton directly alongside an increase of mirid bugs, one of these secondary pest species, which is now causing major infestations on many farms in the region. What makes matters worse is that mirid bugs are a tough species compared to bollworms, sometimes requiring farmers to spray 10-15 times more than they did previously.

The promise of bigger yields and reduced insecticide costs was enough to convince the majority of farmers to switch to Bt cotton. But despite the mass adoption of this so-called helpful technology, cotton remains the most pesticide intensive crop on the planet.

Although it accounts for just 2.5% of the world’s agricultural land, cotton manages to use 16% of the world’s insecticides, and 7% of herbicides. The cotton industry alone spends 2 billion dollars per annum on all these chemicals, so we can assume that there’s significant vested interest in their continued use.

It’s beyond dispute that the unnatural properties of Bt cotton, and the associated knock-on effects, have been a clear-cut disaster for many farmers, producing a whole host of environmental issues much more scary than the bollworm that it was designed to eradicate.

Humanitarian issues

Unfortunately the problems don’t stop here. As farmers spray more chemicals in an attempt to protect their livelihoods, their land is actually becoming less fertile, due to soil degradation and the subsequent collapse of ecosystems. This means yields are now declining in spite of increased production costs on pesticides and GM cotton seeds, sold by the likes of Monsanto.

Given that 60% of the world’s cotton is produced by small hold farmers, many of whom live on the edge of the poverty line, it’s not difficult to see how they can get caught in a bind with these giant agribusinesses that once promised greater security.

As a cash crop, cotton is particularly vulnerable to changes in market price, and weather conditions. During a bad season a farmers income can fall below production costs, driving them into debt, and forcing them to borrow money in the hope that next year’s harvest will bridge the financial gap.

In developing countries the GM cotton industry has become a textbook example of the toxic combination that’s created when financially vulnerable people become reliant on irresponsible multinationals. Thousands of smallholders have now abandoned their farms due to the adverse effects of Bt cotton, but even more tragic is the reported connection to hundreds of suicides. In the indian cotton belt of Vibardha, where Bt cotton is abundant, they reported a dramatic rise in the number of farmers taking their own lives in 2006. Exactly the time when Bt cotton should have been helping these same farmers to prosper.

Further to this, in 2016 the US department of labor reported that forced child labor still existed in the cotton industry of 18 countries, including some of the worlds largest producers, such as China, India, Pakistan, and Brazil.

There is no doubt that conventional cotton is stuck in a vicious cycle with consumer demand and market forces driving production to a level that it is simply unsustainable. In an attempt to keep up, farmers in some of the poorest regions of the world have adopted new technologies and systems, which have provided short term benefits at serious long terms cost. They have been left with less fertile land, more debt, and a dependency on the multinationals that sell GM seeds and pesticides.

We can safely conclude that conventional cotton is indeed a dirty crop, pushing people and nature to breaking point in many parts of the world. So, is there a way to redirect this industry towards a more sustainable future?

Organic Vs GM Cotton

There’s an awful lot written about organic cotton, but first it helps we understand what it actually is. Broadly speaking, organic farming uses non-GM plants, and prohibits the use of synthetic fertilisers or pesticides, with the exception of a few that are allowed on regulation. By principal it also seeks to promote biodiversity and maintain soil fertility wherever possible. There is no doubt that organic cotton has good intentions.

Spoiler alert - When it comes to water consumption there are numerous articles suggesting that growing cotton organically, by definition, uses less water than the GM alternatives. Some sources suggest that it requires up to 88% less water, which would be great!

The real story is not so simple. In reality 40% of the world’s cotton is actually ‘rain fed’, meaning that it grows without irrigation that draws water from natural reservoirs. The water footprint of these farms is much smaller, and it’s these same farms that produce 80% of organic cotton. As a result, it’s not the organic version of the cotton plant that uses less water, but instead the agricultural practices associated with its production.

This is not a bad thing, but it does mean that the headlines purporting that organic production saves oceans of water by the day, can be somewhat misleading. Biologically it wouldn’t make sense, as organic and GM cotton varieties are practically identical, minus a few mutations in the DNA.

What this means is that if all the world’s cotton production switched over to organic plants tomorrow, we would still have a big problem with water. The overriding issue is that we insist on growing cotton in areas without a suitable climate - Ok, spoiler over.

The UpSide Of Organic Farming Practices

We can now discuss the genuine positives associated with farming cotton organically, and there are many.

Sticking to the water theme, one thing that good organic practice will ensure is cleaner water. The prohibition of synthetic pesticides and fertilisers can reduce the acidification of both land and water by up to 70%, compared with conventional GM cotton.

For the local ecosystem this helps maintain the natural balance. Right from the bottom of the food chain, plants, microorganisms and insects can thrive, thereby maintaining a healthy base for the nutrition of other species. It’s good news for aquatic life too, as no synthetic fertilisers means natural levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in the water system, and this causes less eutrophication.

Many sceptics of organic farming practices will point to lower yields as it’s achilles heel. Short term at least, Bt cotton does increase yields and permit more intensive farming practices. However, in depth comparative studies actually suggest organic farmers are still better off. Input costs are typically 10-20% less for organic farmers, and their product sells for a premium price around 20% higher than conventional cotton. Consequently even when organic cotton is grown in rotation with other non-premium crops, these farmers make 10-20% more income overall. What’s more, the natural approach of organic farming means that soil fertility is maintained in the long run, thereby mitigating against the diminishing harvests often seen after consecutive seasons of growing Bt cotton.

By demanding less chemicals organic farming practices also help reduce the production of industrial pesticides and fertilisers, a process which is in itself bad for the environment. Fertilisers alone account for 1.5% of the world’s energy consumption, leaving a sizable CO2 footprint.

Overall, there is no doubt that organic farming can improve the livelihoods of small holders, whilst helping protect the vital eco-systems that maintain biodiversity and fertility of the land for generations to come.

There is however a big hurdle to the expansion of organic farming in many countries. To achieve organic certification, farmers must undergo a 2-3 year conversion period, during which yields are typically lower than normal, because the land has not yet recovered sufficiently to reap the benefits of the organic system. This creates a huge barrier to entry for farmers who are already struggling to make ends meet, and perhaps helps explain why today just 1% of global cotton production is certified organic.

A Sustainable Outlook For Cotton Production

We need to play our part

Many people, especially those from Europe and parts of the US, have never even seen a cotton field, let alone tried to understand how cotton production is really affecting the planet. This only highlights our disconnection from the social and environmental effects of it’s cultivation, whilst allowing us to ignore the part that WE play in the big picture.

For sure, farming by organic means makes cotton less of an environmental burden, so if we have a choice, we should always buy organic [L]. The more we insist on buying organic material, and rejecting the alternatives, the more we oblige the industry to shift towards more sustainable organic practices.

Be prepared to pay a bit more

Knowing the complications associated with organic farming and the tight profit margins, we should also be prepared to pay more for this product. To make a real difference, we need to say goodbye to $5 dollar t-shirts, a price that is simply unsustainable for both the environment and the livelihoods of farmers.

Look out for certification that ensures organic standards are met throughout the supply chain. Organisations like Organic Content Standard (OCS), and Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS), are common, and easy to find [link to our product pages]. Other certificates like the Fair Trade Foundation also ensure that farmers have been paid a living wage.

At a policy level, more needs to be done to support small hold farmers who want to convert to organic production. Right now the financial burden of conversion creates a huge barrier to entering the organic market, leaving some farmers trapped on Bt cotton and synthetic pesticides, even if they want to change.

Buy less, and buy to last

We can rant all day about the benefits of organic compared with conventional cotton, and no doubt some people have arguments to the contrary. The basic fact remains that we are consuming too much cotton, whether organic or not. To become truly sustainable we have to do away with throw-away culture.

Think about all that water, and all those pesticides. Now take a look at those clothes you are wearing, and think again. Buy less, and when you do, buy to last.

Be the first to know when Europe's top ethical brands are on sale, sign up to our newsletter here

Be the first to know when Europe's top ethical brands are on sale, sign up to our newsletter here